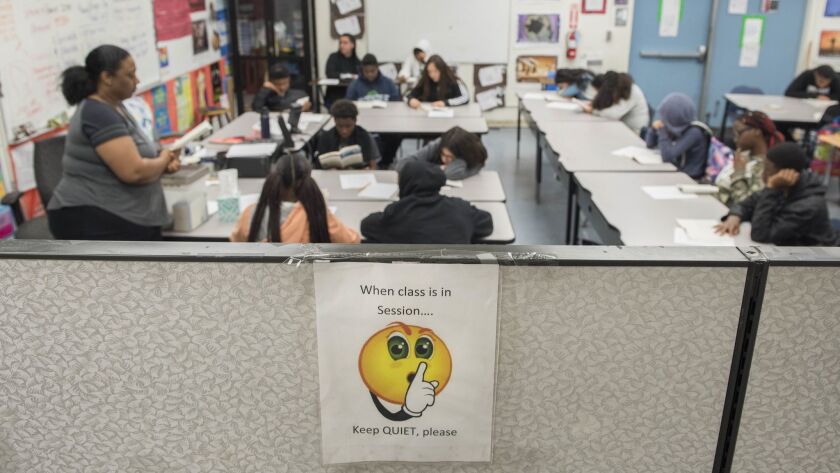

Students at Magnolia Science Academy 3 learn in a makeshift classroom created with dividers in the school’s office space. Efforts to rent empty additional empty space on the campus of Curtiss Middle School in Carson have hit roadblocks.

(Nick Agro / For The Times)

The eighth-grade English class at Magnolia Science Academy 3 met last semester in an unusual setting: a carved-out rectangle in the school’s office, formed by portable dividers.

Cramped quarters have forced such coping strategies at the charter school, which would like to rent more space at the roomy campus it shares with Curtiss Middle School in Carson. But so far, a solution to its problem has proved out of reach.

Under state law, charters — which are privately operated — are entitled to a “reasonably equivalent” share of space on public school campuses. The Los Angeles Unified School District says Magnolia already occupies its fair share, and though the district could choose to provide more space, it won’t — for reasons officials have not clearly explained.

Nowhere are the challenges and tensions of such forced collaborations more acute than in L.A. Unified, which has more charters — 225 — than any other school system.

Access to district campuses is important to charters because land and construction costs are prohibitive. And the competition for students has become especially intense as overall enrollment in L.A. Unified has declined, threatening the viability of many schools. New charters continue to open — their growth funded by philanthropists — and they now enroll nearly one in five district students.

Los Angeles Unified has sharing arrangements at 80 campuses, more than any other district because of its size and because the California Charter Schools Assn. repeatedly has pursued litigation to enforce state rules.

But one school’s success often is seen as being at the expense of the other. Parents and teachers at numerous schools have led unsuccessful protests to keep a charter off campus. At some campuses, the district has gone so far as to demolish outdated and outlying buildings, which increases playground areas while also deterring charters from claiming available classroom space.

To school board member Richard Vladovic, putting a charter on an unwilling L.A. Unified campus almost never pans out.

“What I’ve seen is animus,” said Vladovic, who represents the Carson area and recently began a one-year term as board president. “I think it’s real bad for kids.”

The complications run big and small.

Magnolia has to throw out unopened milk every day because it doesn’t have access to refrigeration in the cafeteria.

The district-run school no longer has a band, but if it wanted to revive the program — which is in line with district goals — it would have a problem. The charter has the wing with the music rooms.

Magnolia has a band but objected to the district’s designation of a music room, with built-in risers, as its classroom for disabled students, because some of them have mobility problems.

To work around that, the charter swapped access to the library for possession of an empty space that used to be a weight room adjacent to the gym. That room has its own bathrooms and the floor is flat.

The two principals are cordial in managing day-to-day issues, although Magnolia Principal Shandrea Daniel has a list of things she’d love to improve. Her assigned “science lab,” for example, has only one sink and lacks such built-ins as Bunsen burners and an eyewash station.

And the small central area between Magnolia’s classroom buildings is where Curtiss keeps its dumpsters.

“What kind of message does that send to my students?” Daniel asked.

Magnolia Principal Shandrea Daniel stands in front of the dumpsters that occupy the area between her classroom buildings. She’d like them removed or enclosed.

(Nick Agro / For The Times)

She’d like the dumpsters moved elsewhere or completely enclosed.

Curtiss Principal Gina Russell-Williams said there has been a “productive and positive” relationship between the schools but declined to comment about ongoing issues.

“My opinion is moot unless the district OKs it,” she said.

Board member Nick Melvoin said that campus sharing is unavoidable under state law and frequently works well. True collaboration, he said, can help students at both schools. He helped organize a retreat last year — funded by a pro-charter group — that sought to build ties between district schools and charters.

At first glance, Curtiss Middle School, with a drab two-story main classroom building, doesn’t look like much of a prize. But with nearly 20 acres, both programs have access to an expansive grass field — a rarity at many district campuses. The children from the two schools stay separated in their own halves and use the gym at different times.

Different schools; different uniforms. Magnolia charter students, left, pass students from Curtiss Middle School, in yellow, during physical education. The playground is permanently split between the two schools.

(Nick Agro / For The Times)

There are lots of classrooms — 59 of standard size and nine smaller ones — and L.A. Unified has been struggling to fill them. The school has 477 students — up from a low of 442 two years ago, but down from 964 less than 10 years ago. Now there are just 170 students from local neighborhoods at Curtiss. Its other students are part of a “magnet,” which buses in students who have chosen Curtiss as an alternative to their own neighborhood schools.

Curtiss, which serves grades six through eight, has its virtues, including a partnership with a local community college that allows eighth-graders to earn college credits, coursework in robotics and computer coding and a new “maker’s space,” in which students carry out class projects that involve hammers, saws and recycled materials. In physical education, students can use rowing machines, an exercise bicycle and a StairMaster.

But the notable growth has been at Magnolia, which started about 10 years ago and peaked at about 510 students this year — at least 40 of them from the Curtiss attendance area. Magnolia takes particular pride in its athletics and its music program and a technology focus that includes a robotics team and computer coding classes. The school’s grade span is six through 12, which allows it to offer Advanced Placement courses in computer science and other subjects.

Students at each school perform similarly on state standardized tests. Both are split fairly evenly between black and Latino students from low-income families.

Magnolia’s growth rests in part on attracting students — about 40% of them — from places such as Torrance, Compton, Inglewood and Long Beach, all outside of the district. But L.A. Unified is obligated to provide space only for students who live within district boundaries.

The district-run school — with fewer students than the charter — is using 38 full-size classrooms and five smaller ones, compared with 19 being used by the charter. Even so, there still are five unused classrooms and four unused smaller rooms in the Curtiss Middle School portion.

An unused classroom at Curtiss Middle School in Carson, as seen through a glass pane on the door.

(Nick Agro / For The Times)

Curtiss has the luxury of setting aside two rooms for testing and four in which students can receive special academic help outside of their regular classes.

Meanwhile, on the charter side, two classrooms are set up using dividers in the office space. Teacher Angela Smith rotates in, as do others. On a recent Monday, her class was studying an essay in which Holocaust survivor Eli Wiesel described his impulse to write.

“Follow along when I read because you’re going to continue on as I ask you to finish my sentence,” Smith tells students.

“Did I write it so as not to go mad or, on the contrary, to go mad in order to — what?”

‘’Understand the nature ...” a few students continue haltingly.

“Keep going,” she urged.

The students continue with more voices and more volume: “… the nature of the madness, the immense, terrifying madness that had erupted in history and in the conscience of mankind?”

On the other side of the divider, where office staff must pass, someone has taped a piece of paper decorated with a shushing emoji that warns: “Keep QUIET, please.”

Magnolia pays L.A. Unified about $310,000 a year for its share of the campus, and Daniel said she would happily pay for more classrooms — money that could go toward programs at Curtiss.

But L.A. Unified isn’t taking the deal — one senior manager suggested that the district would not provide more space until the charter dealt with unpaid fees well in excess of $250,000. These potential penalties were a result of Magnolia overestimating how many of its students live within district boundaries, he said.

Magnolia officials say the issue of unpaid fees is news to them, and the district subsequently said that the matter is under review.

The district and the Magnolia organization have clashed before.

Several years ago, L.A. Unified faulted Magnolia schools for importing nearly 100 teachers and other school employees from Turkey in possible violation of rules on overseas hires.

Magnolia has discontinued this hiring, but L.A. Unified refused to reauthorize the charter of Magnolia Science Academy 3. The school was on the verge of being closed until the L.A. County Office of Education stepped in to renew the charter. The county office now oversees the school, but L.A. Unified must still house it — an arrangement that rankles some in the district.

Curtiss Principal Russell-Williams tries to stay above the fray on the competition for resources and students.

“All schools have challenges because parents have choices,” she said. “That just goes without saying for every school.”

No comments:

Post a Comment